Understanding Addiction, Recovery, Mental Health, and More... Through Faith

More Posts

Tramadol’s Harms Outweigh Its Benefits

Do the potential harms associated with tramadol outweigh the risks?

Bedlam in the “Postdenominational” Church, Part 2

NAR leaders who claim to be modern apostles have failed to show the office is ongoing.

Marijuana and Psychiatric Illness

We need to slow the rush to legalize recreational marijuana and give scientific research time to catch up.

A New Adulterant for Opioids Called “Flysky”

There’s a new opioid cocktail called “flysky,” coming to an overdose near you.

Bedlam in the “Postdenominational” Church, Part 1

Does the church need the fivefold ministry to fulfill its mission of advancing God’s kingdom?

The Quest for the Genetic Basis of Schizophrenia

Current research suggests that genetic testing explains less than 1% of whether someone is schizophrenic.

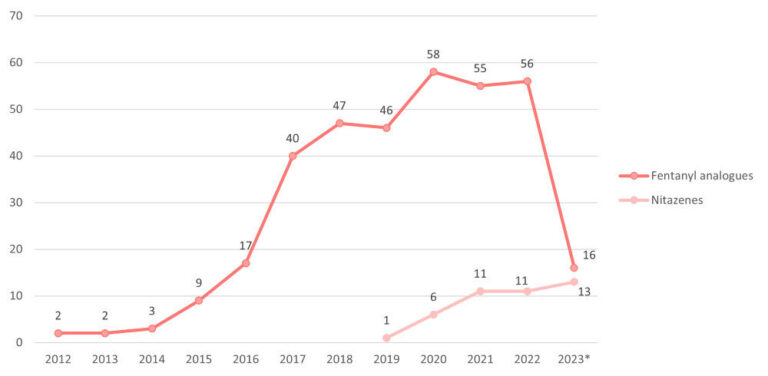

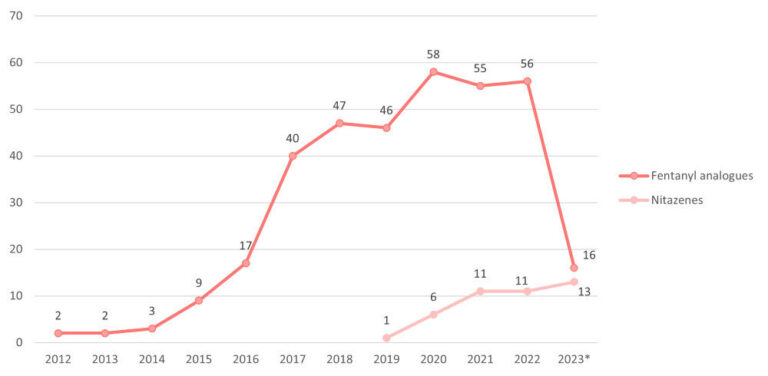

Could Nitazenes Replace Fentanyl?

Are nitazenes replacing fentanyl in illicit opioids?

Miracles as a Man?

Bill Johnson seems to be confused when he talks about Jesus Christ. He said Jesus could not heal the sick; nor could he raise the dead.

Tramadol’s Harms Outweigh Its Benefits

Do the potential harms associated with tramadol outweigh the risks?

Bedlam in the “Postdenominational” Church, Part 2

NAR leaders who claim to be modern apostles have failed to show the office is ongoing.

Marijuana and Psychiatric Illness

We need to slow the rush to legalize recreational marijuana and give scientific research time to catch up.

A New Adulterant for Opioids Called “Flysky”

There’s a new opioid cocktail called “flysky,” coming to an overdose near you.

Bedlam in the “Postdenominational” Church, Part 1

Does the church need the fivefold ministry to fulfill its mission of advancing God’s kingdom?

The Quest for the Genetic Basis of Schizophrenia

Current research suggests that genetic testing explains less than 1% of whether someone is schizophrenic.

Could Nitazenes Replace Fentanyl?

Are nitazenes replacing fentanyl in illicit opioids?

Miracles as a Man?

Bill Johnson seems to be confused when he talks about Jesus Christ. He said Jesus could not heal the sick; nor could he raise the dead.